Human relationships are at the heart of how Baha’i teachings influence society as well as individuals. Some thoughts from presentations at the 2020 conference of the Association for Baha’i Studies:

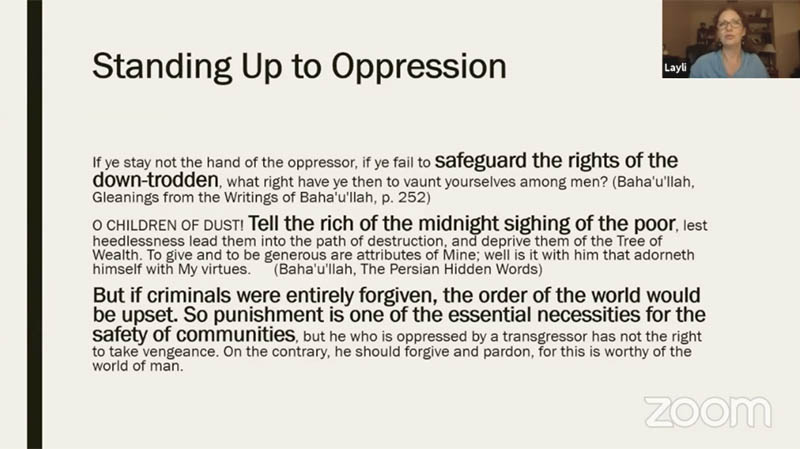

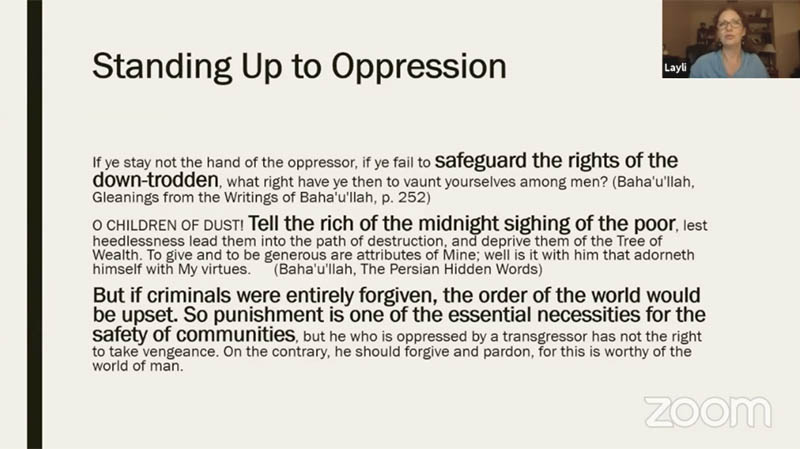

Presentation: “Justice: A Path to Unity,” Layli Miller-Muro, July 27

Justice’s purpose in this world is to make unity possible, said Layli Miller-Muro in a talk that shared her evolving understanding of Baha’i teachings on a complex concept.

Ironically, Miller-Muro said, the first stage of the process of justice does not look unifying. When someone is wronged, justice requires voicing unpleasant facts or confronting painful truth. Such a demanding, discomforting action may appear to divide people.

Still, while society has a duty to uphold justice, Baha’i teachings say the vital role of the individual is to forgive and show compassion, Miller-Muro said. Both responsibilities must be exercised to reinforce an effective, complete system that works for improvement and allows unity to emerge.

The organization provides legal advocacy for immigrant and refugee women suffering human rights abuses. Coming from many parts of the world, chiefly from Latin America and Africa, its clients are survivors of domestic violence, human trafficking, female genital mutilation, rape, child marriage, forced marriage or other acts of violence and oppression.

The Baha’i standard is challenging, Miller-Muro said. “You can’t talk about justice in a Baha’i paradigm without also talking about forgiveness,” she said, and typical responses of “ego, weakness, anger, emotion, hurt, and resentment” are all obstacles to understanding and achieving justice.

She quoted Baha’i guidance that urges: “If others hurl their darts against you, offer them milk and honey in return; if they poison your lives, sweeten their souls; if they injure you, teach them how to be comforted; if they inflict a wound upon you, be a balm to their sores. …”

At the same time, the exercise of justice is “a right of the people,” even as it can involve empathy and reconciliation as much as process and law.

And to preserve that right, society has a collective duty to correct, and often punish, for the protection of all. She cited a warning from Baha’i writings: “Kindness cannot be shown the tyrant, the deceiver, or the thief, because, far from awakening them to the error of their ways, it maketh them to continue in their perversity as before.”

Individuals need to participate in this, whether to speak their own truth or to intervene on someone else’s behalf.

Then she offered a humble disclaimer: “I don’t fully understand it. … I’ve tried personally and professionally.” We all fail sometimes, she said, and could practice forgiveness with ourselves.

Still: “We’re all souls growing,” she said. “We deserve mercy and compassion as we deserve boundaries and consequences. … We have to get to the point where they can live in the same heart and the same society.”

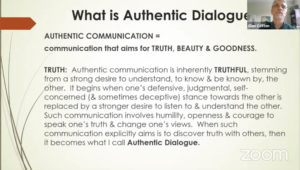

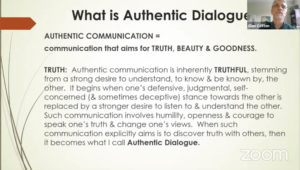

Presentation: Authentic Dialogue, Moral Empowerment, and Civilization Building, July 29

Truth, beauty and goodness. Aiming for those qualities can help us make dialogue and relationships with others more authentic. That effort advances our individual maturity and strengthens the foundation of a just and peaceful world, says Glen Cotten, a university and adult educator in North Carolina.

He told of interviewing high school students who were in a racially mixed workshop to discover a more authentic dialogue with each other. One workshop participant spoke for many, he said, reflecting that as she worked to build an authentic conversation, “I just felt like I was really hearing that person. … it’s like letting your outer shell go so you can see the connection that was already there.”

Cotten is one of several Baha’i scholars exploring this sense of authenticity, flowing from classic principles and informed by Baha’i teachings.

His approach to the complex concept of authenticity, he said, starts with ideas stated by the ancient Greek philosopher Plato: that the quest for truth, beauty and goodness distinguishes humans from other creatures, and the path can only be fully explored if we have dialogue with others.

Beauty: “This kind of communication recognizes and honors the unique value or beauty of each participant,” rather than placing value on sameness, he said. “We aim to co-create a beautiful conversation in the same way that jazz musicians carefully listen to each other when they improvise … [and create a] sublime musical moment.”

Goodness: Such communication is “an inherently moral act that fosters restorative justice, love and unity in human relationships.”

Cotten said these principles resonate with Baha’i guidance on the process of consultation, working together to discover truth in a spiritual atmosphere.

Shoghi Effendi’s guidance in The Advent of Divine Justice about how people of different races have differing responsibilities in working toward racial justice, Cotten said, points out another element of authenticity. “We can and should derive strength from the understanding that we are all ultimately spiritual beings,” he said. But to aid in the process of reconciliation in a world of persistent inequality, “we must take responsibility for the position we are born into.” Shoghi Effendi’s advice reflects the grievous wounds carried by Black people, and it instructs those in the more-advantaged population to continually examine themselves for any trace of superiority, educate themselves, and take initiative.

In response to audience questions, Cotten said authentic dialogue might not always feel joyful. “We should expect that there will be all the human emotions involved,” he said; it could sometimes feel like repentance, “the sense of really having humility to recognize that what I’m saying is hurting somebody else.”

But it is made meaningful by how we act in response. Harking back to Plato’s principles, he said, “Goodness is about morality and morality is about action” — and that nourishes an authentic relationship.

Meet the Author: Stephen Beebe, Baha’u’llah, the West, and the Birth of Modernity, July 31

Two very different stories are revealed in the title and subtitle of Stephen Beebe’s Baha’u’llah, the West, and the Birth of Modernity: An Essay on the Awakening of Humanity.

Its subtitle alludes to the story of masses who dared to dream of freedom and empowerment as the Industrial Age unfolded but had their gains cruelly reversed at every stage by their rulers and economic overlords.

With the appearance of Baha’u’llah, Prophet-Founder of the Baha’i Faith, these two forces of history converged, Beebe told his audience.

Baha’u’llah took to task the crowned heads and religious leaders of the day — Napoleon III, Pope Pius IX and Tsar Alexander II among them — and gave voice to the yearnings of the voiceless.

Yearnings that are being heard louder and louder today as a new cycle of human power takes root amid the flowering of a Baha’i-initiated community-building process that gives people the tools to transform lives and society.

“We’re not going to be getting headlines for doing a children’s class,” Beebe acknowledged. “But it’s every bit as important as any event of the 19th century.”

![]()

![]()

Whether you are exploring the Bahá'í Faith or looking to become an active member, there are various ways you can connect with our community.

Please ensure that all the Required Fields* are completed before submitting.