Constructive resilience, especially as it applies to racial justice, was a strong thread through many presentations at the 2020 online conference of the Association for Baha’i Studies. Here are a few (more are to be added soon):

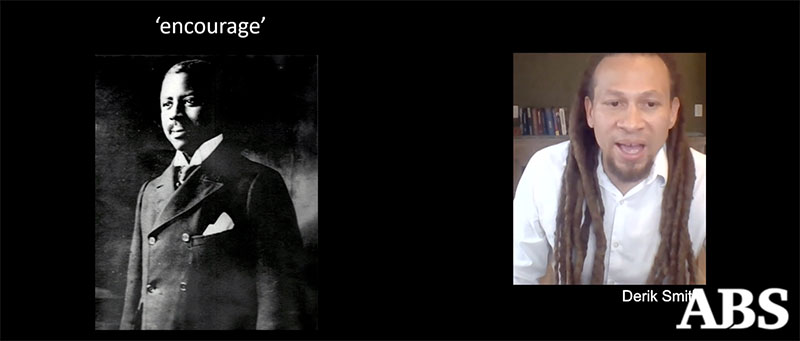

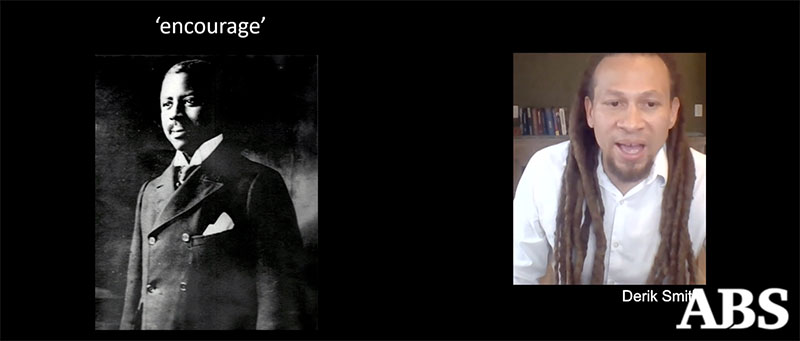

Keynote presentation: The New Black Power: Constructive Resilience and the Efforts of African American Baha’is, July 25

Derik Smith, a literature professor at Claremont McKenna College in California, demonstrated through various examples how a “radical power,” available spiritually to everyone, has shone out in the actions and example of various Black Bahá’ís — a power that “glints through clouds of oppression.”

This guidance, he said, can help shape a new vision of Black power that not only dismantles mechanisms of oppression, but also contributes to the building of a just society, with individuals and communities in concert, building institutions that “embody the principle of the oneness of humankind.”

It will be painful striving to advance this vision in the midst of “the choking oppression that surrounds us,” he acknowledged. “We must learn about how we can, in this moment, prefigure the world that we want to see in the future,” acting with the resilience to “move forward with our building after we have been knocked back … get up and start building again after we have been knocked down.”

And through stories of courage and images exuding hope, Smith shared glimpses of such resilience and of a “unified, loving power that welds together hearts.”

This collective power of love, service and reliance on God “is not specifically Black, of course,” Smith said in summation, but rather “like water, taking on the color” of whoever channels it. “This power does not contend or compete with any other power, Black or otherwise.” It cannot be hoarded, he said, “it can only be released. … It unifies and bonds. … It is transformative.”

Presentation: Breaking Free of an Epistemology of White Ignorance, July 31

Research and experience overwhelmingly prove that racial injustice is rife in America’s communities and institutions. But “white ignorance” — the denial of such injustice — persists on a wide scale because many people cling to the stories they have inherited, said Elizabeth Allen.

A goal of her presentation was to synthesize Baha’i writings with current Critical Whiteness Studies research. She approached it through a lens of epistemology, a study of the origin, nature, methods and limits of human knowledge.

She described whiteness as an ideology — a mental or moral framework — that many people use to make sense of the world. This or other racial ideologies may affect:

Whiteness, she said, is inseparable from white supremacy, “a social, political and economic system that we have inherited as a nation for the purposes of preserving the land, wealth and power white men have accrued by colonizing North America.”

Racism is interlinked with that frame of thought. Racism is not just prejudice, she said; it is race-based prejudice that is “reinforced by systems of power.”

Baha’is are called to view the human race as one and to work to eliminate prejudice. Specifically, Baha’is in America are urged to “weed out, by every means in their power, those faults, habits, and tendencies which they have inherited from their own nation.”

To illustrate some tendencies in U.S. culture, Allen shared historical examples of how whiteness has been perpetuated as “the American way.”

Manipulation and fear are used to perpetuate racism through the dominant social narratives. “To say racial things in non-racial ways masks the systemic, the structural and institutional racism,” Allen says. Some examples of such narratives:

Allen also described how white emotion is often weaponized to suppress whites’ own shame and guilt and to put people of color in their place. She shared the infamous example, widely posted in social media, of a woman in New York’s Central Park who made an emotional call to the police implying she was being threatened by a Black man, after he had asked her to comply with the law and leash her dog.

“There is work that we have to do at an individual level to begin to unpack and untangle all of these ideologies,” says Allen. “We have a choice to act white, or not to act white.”

American Baha’is have been challenged by Shoghi Effendi, the Guardian of the Baha’i Faith, to cultivate “rectitude of conduct, an abiding sense of undeviating justice and the freedom from racial prejudice.”

In the spirit of taking oneself into account regularly — also a Baha’i teaching — Allen suggested that white people ask themselves these questions:

“Are we being truthful to ourselves concerning the ways we own up or not to our false sense of superiority? What would a rectitude of conduct look like” in the face of the challenging issue of racism?

“How are we addressing our complicity when we feign ignorance of the ways whiteness affects people of color through racism in our Baha’i and broader communities?”

Meet the Author: Crossing the Line, Richard Abercrombie and JoAnn Borovicka, July 31

Crossing the Line: A Memoir of Race, Religion and Change is the story of Richard Abercrombie’s emergence from simmering despair as a young African American in 1960s Greenville, South Carolina, as he struggles with racism and a slide toward delinquency.

After Abercrombie’s unexpected encounter with the Baha’i Faith in 1960, he faces a different kind of challenge with race. His family members worry about him interacting with whites. He discovers hope as he embraces this religion that speaks to racial equality and the fundamental unity of religion, and offers peaceful strategies for social justice. The book is written as an action story for young people.

“I encourage all young people to strive for change,” Abercrombie said. “We are in a process right now where tremendous change is in the making. But it has to be brought about in the right way. … It has to be done peacefully.”

Said his co-author, JoAnn Borovicka, “The book does address the question of what is the Baha’i approach to social action. It was a challenge in the ’60s and it is a challenge now.”

The book started years ago as a 10-page account Abercrombie wrote about his spiritual journey. While serving at the Baha’i World Center in Haifa, Israel, he was encouraged to make the story more complete by Kiser Barnes, then a member of the Universal House of Justice, global governing council for the Faith. After some years he enlisted the help of Borovicka, a family friend who is a writer and researcher.

In many hours of interviews over three years, Abercrombie dug deep into his memory to describe what his 12-year-old self was thinking, feeling, and even carrying in his pockets. A great deal of trust grew between him and Borovicka, he said, partly because of “our close association in Baha’i and non-Baha’i settings.”

“The reality of white domination being a constant heaviness of every African American — whether they are in the Baha’i community or not — is something that I’d like to talk more about in the future,” Borovicka said. “My hope and desire right now is to bring more attention to that aspect of working towards a solution for racial prejudice.”

The authors also hope readers will see how principles and dynamics of the Baha’i community gradually unfold in the book.

Youth have capacity to see truth even when society submerges it in hypocrisy and lies, Abercrombie noted. “No matter your situation, change is possible. It takes courage to change and youth have great capacity to take radical action for change.”

![]()

![]()

Whether you are exploring the Bahá'í Faith or looking to become an active member, there are various ways you can connect with our community.

Please ensure that all the Required Fields* are completed before submitting.