‘Abdu’l-Baha, son of the Founder of the Baha’i Faith, was a powerful contributor to a framework of Baha’i thought, even as He served as the “embodiment of every Baha’i ideal” and maintained the unity of the Baha’i community as its appointed leader for nearly three decades, said Paul Lample, member of the Universal House of Justice, the world governing council of the Baha’i Faith.

The conference’s theme, “In the Footsteps of ‘Abdu’l-Baha,” pays tribute to the 100th anniversary of His passing in 1921. Click here for an overview of the conference.

Much as in 2020, this year’s nine-day conference was conducted through online video presentations. However, this year most programs were recorded and posted in advance, so that participants could view a lecture-style presentation at their convenience. Live discussions with the presenters were also scheduled.

A few online discussions were unrecorded, including discussions of the methodologies of generating knowledge, inspired by the studies and thoughts of people in areas such as education, social science and economics.

Lample’s talk, “Reflections on the Challenge of Our Time,” touched on some central purposes of Baha’u’llah’s religious teachings: not just to enrich people’s spiritual lives one by one, but also to change relationships between individuals, communities and institutions. “The institutions of society move from where they are to become a framework of a new world order. Society moves from a material-driven society to one that becomes an ever-advancing spiritual civilization. And human beings are re-created to become a new human race,” he said.

‘Abdu’l-Baha Himself is one of the greatest gifts from Baha’u’llah, as He provided clarification of the interplay between spiritual and social principles in the Baha’i teachings, Lample said. The world is used to contests for supremacy between people who have differing moral ideas, he said. But in contrast, “‘Abdu’l-Baha’s power of thought helps us to transcend the existing moral framework in the world” and build unity in diversity through deeds as well as words.

Focus on ‘Abdu’l-Baha

Given the focus of the conference, it was natural that many sessions centered on ‘Abdu’l-Baha and His influence on thought within the Baha’i community and beyond. Summaries of a few:

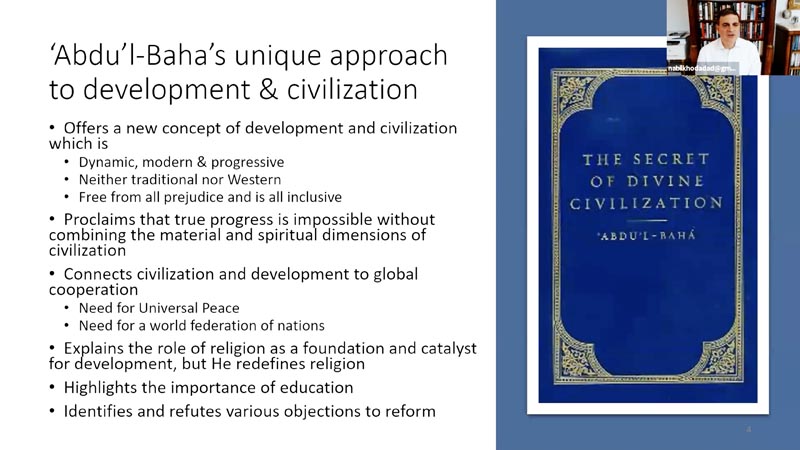

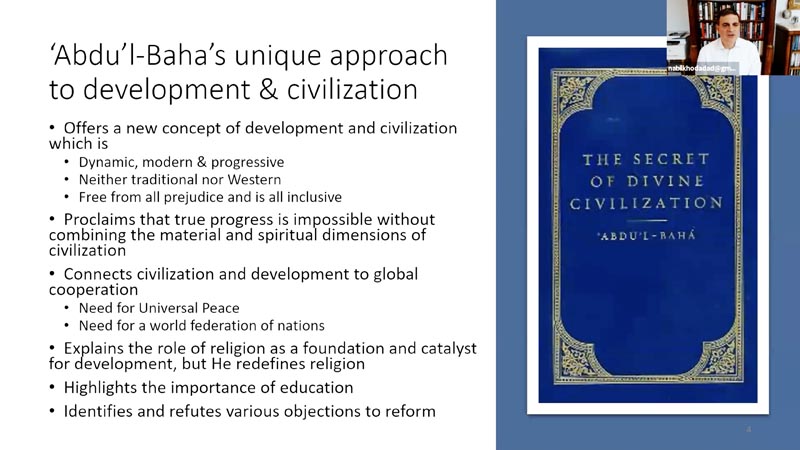

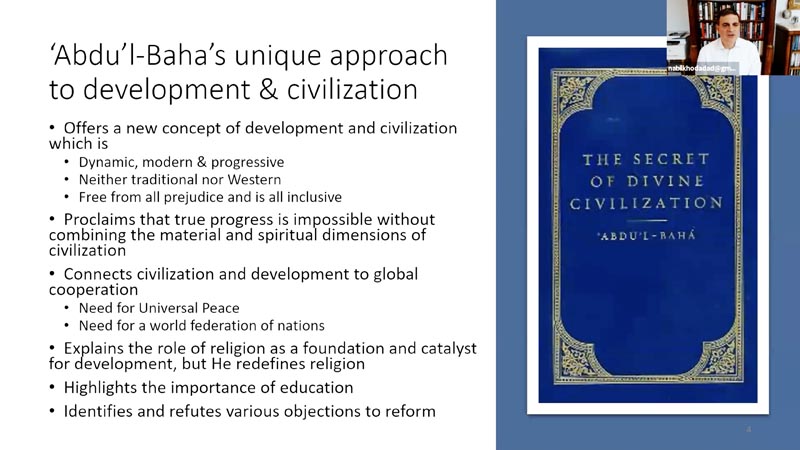

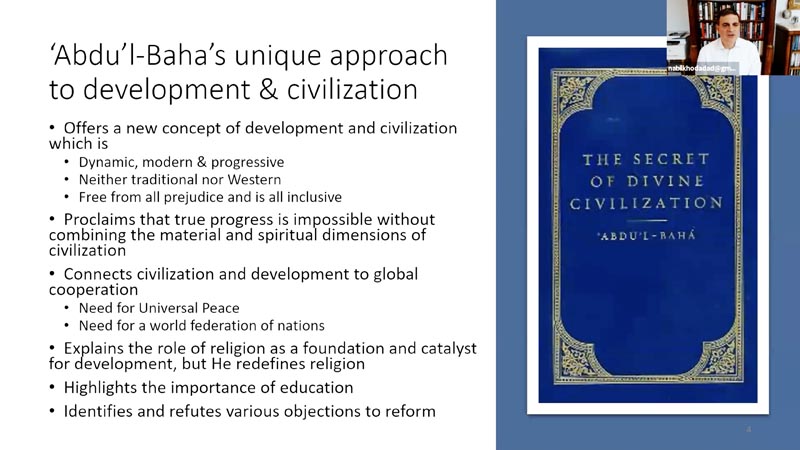

The book’s unique concept of development in society is based on the need to combine both the material and spiritual dimensions of civilization, the essential roles of global cooperation and freedom from prejudice, and the role of authentic religious teachings as the core of development.

This book was offered as a contribution to a social and governmental reform movement in 19th-century Persia. But its ideas for transforming society, based on Baha’u’llah’s social and spiritual principles, range far wider than its own time and place — it “resonates even more today than it did when it was written a century and a half ago,” said Khodadad. He noted that the COVID-19 pandemic is one current-day phenomenon that creates an opportunity to reflect on how people, communities and institutions relate to each other.

Less known, said author Paul Hanley, is that He encouraged agricultural practices that are today considered regenerative: planting of a variety of crops, with a rotation that includes legumes and cover crops; construction of irrigation systems; use of livestock to diversify income and help with fertilization; and use of trees to reduce malarial swamps and cool the environment. He also helped modify the relationship between landholders and farmers “to give the villagers a larger share of the income,” and incorporated wider social and spiritual ideas such as a diverse local economy, a “strong focus on moral education” for children, and consultative decision making.

The spirit of these approaches remains relevant, he noted, as more than a third of the world’s population makes a living — often at bare subsistence level — through farms, forests or fisheries.

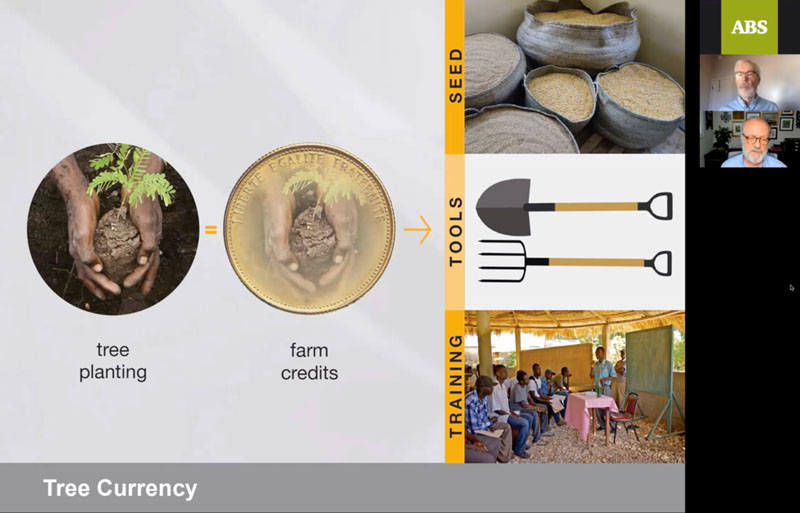

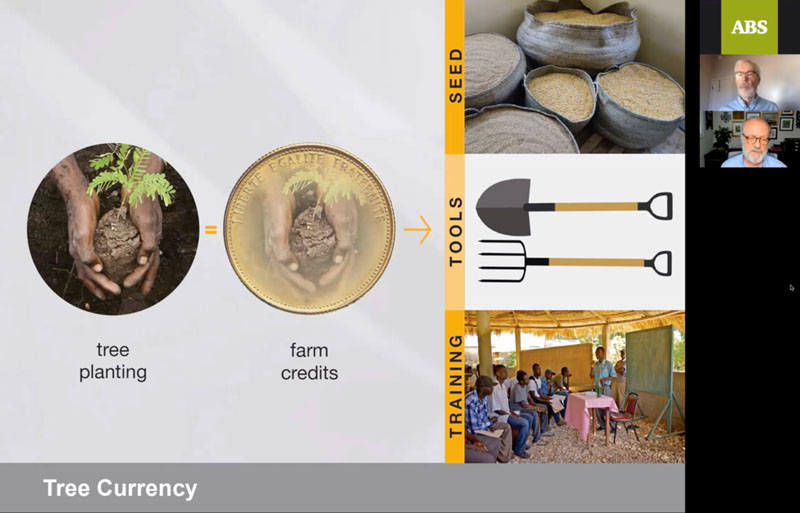

Modern echoes of this well-rounded approach emerged as Hugh Locke talked about the Smallholder Farmers Alliance in Haiti, which has supported small farmers in planting more than 8 million trees in an island country where forests have been virtually eliminated. The complex project, developed in constant consultation with local farmers, opens avenues for them to acquire high-quality seeds, tools and training; connects them with markets for their crops; facilitates their common efforts to acquire livestock; and produces materials to educate children on the environment and advancement of women. It is also helping the farmers restore a lost custom of mutual assistance at harvest time.

“Every action is based on community consultation, whether it’s deciding on who gets a microcredit loan, who gets the goats, which farmers are able to grow cotton, what seeds are requested in any given season, what tools are needed by the community,” Locke said.

‘Abdu’l-Baha and the Peace Movement Reconsidering the Civil Rights Movement in the Footsteps of ‘Abdu’l-Baha

‘Abdu’l-Baha’s Prophecy — American Indian Ways of Thinking and Being as a Form of Holistic Illumination

‘Abdu’l-Baha’s Tablet to Dr. Forel

Learning from ‘Abdu’l-Baha in a Society Characterized by Ageism

‘Abdu’l-Baha as Architect of the World Order of Baha’u’llah

Remembering the Master: Two New Books

Encouraging the Arts During the Ministry of ‘Abdu’l-Baha: the Services of Master Calligrapher Mishkin-Qalam

Constructive resilience

Many of the above topics perpetuate a theme carried over from past ABS conferences — how Baha’i teachings can nurture constructive resilience in the face of oppressive social currents. Among the additional presentations that underscored this topic:

For much of its history, BIHE operated essentially underground in the homes of Baha’is, which were subject to periodic police raids and confiscations of supplies and equipment. Even as more classes were conducted online, students have faced the stress of learning in isolation — in addition to uncertainty whether they might be arrested and jailed at any time.

“Stories like this were not uncommon,” said graduate student Kimiya Tahirih Missaghi. She has interviewed BIHE alumni who have since moved to North America, and her analysis of their responses reveals a distinctive quality of resilience that goes beyond merely adapting or “bouncing back” in an adverse situation.

As co-presenter Shakib Nasrullah confirmed, that resilience extended to the desire to benefit society, with help from community support and fed by a deep conviction, founded in the Baha’i teachings, of the vital importance of education and the sciences. Other relevant spiritual values included “nonviolence, detachment … they didn’t develop hate against their oppressor,” Nasrullah said.

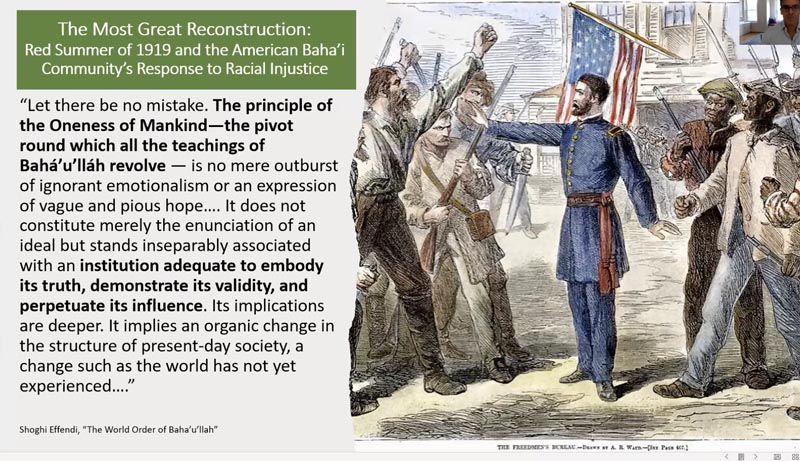

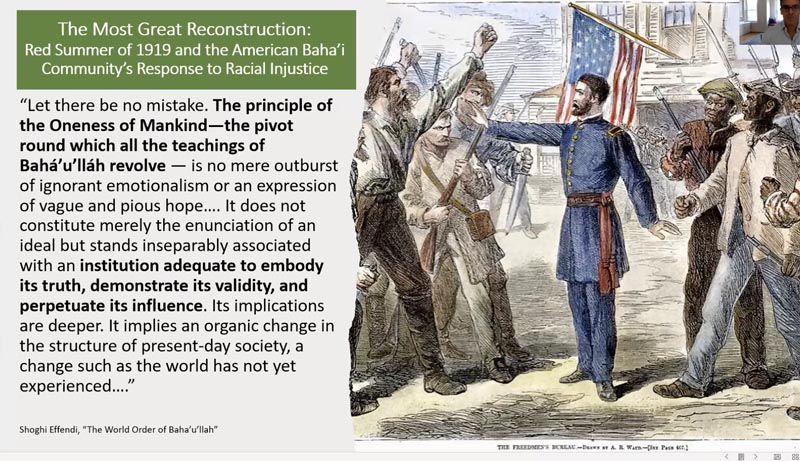

The first four conventions, 1921–1924 in several East Coast cities — arranged with the aid of such organizations as the NAACP, the Urban League and the League of Women Voters — were particularly effective in promoting the oneness of humanity among religious and political leaders, Khadem Khodadad said. (Click here for an overview of the beginnings of the movement.) Their emphasis on spiritual unity rather than any particular political agenda attracted thousands, including many civic officials and respected Black thinkers.

“By standing at the vanguard of discourse and forging bonds with communities at the center of Black thought, ‘Abdu’l-Baha and the American Baha’i community were engaged in a revolutionary type of social action, refusing to shy away from the most contentious issues of the day,” said Khodadad. “It’s a legacy we all now inherit and we must seize, with the audacity that ‘Abdu’l-Baha urged [in] our spiritual forebears.”

Even during the bitterest oppression in the Americas, he said, African-American communities cultivated “initiatives that minister to body, mind and soul alike, to form mutual aid societies, formal and informal tutoring, … collective effort and pooling of material resources … a ferocious commitment to education under even the most dire circumstances.”

These efforts reflect a quality that has come to be known within the Baha’i community as “constructive resilience,” he said. A protagonist-centered approach to Black history can “shed great light on the distinctive character and meaning” of the Baha’i community-building process as it unfolds on this continent — fortifying a spirit of generosity, relationship building, and willingness to work for the good of the whole that can be found at the core of Baha’i activity.

These principles find reinforcement from the Baha’i teachings of unity in diversity she was brought up with, as well as attitudes toward knowledge encouraged in Ruhi materials. Even something as simple as sitting in a circle on the same level as students, a common practice for tutors in study circles, helps every student realize “that there is a place for them, and that all knowledge is sacred.” It also increases trust as it dissolves a teacher-student power structure that many take for granted.

Teachers and students together discuss principles from such scholars as bell hooks or Paulo Friere. Sometimes they develop courage to ask questions they had been made to feel were “forbidden,” she said — for instance, why their schooling is centered so much on rote learning. “Students are eager to participate,” she said.

These and other elements help to structure “dynamic spaces of consultation and dialogue” where students form relationships of respect, encourage each other to learn in action, then later reflect together on the results of those actions, and “go out and try again.”

They touched on how certain racial and cultural groups, women of all backgrounds — and relationships and power dynamics between them — have been represented and portrayed on screen over the years.

“Film has the capacity to be an effective tool for engagement in the discourses around race and gender, and the narratives we’re being offered — both positive and problematic,” Wright said. But audiences, she noted, often ignore or take for granted the narratives that lead to people’s degradation — potentially giving those narratives great influence over our inner lives.

“In the spirit of independent investigation of truth, it’s necessary for us to approach our movie watching with a critical eye,” she said, “so that we can unpack what messages are being delivered, rather than just taking movies in as pure entertainment.”

Power to the Pupil: Towards a New Black Liberation Theology Within the Framework of the Baha’i Faith

Combating Corruption and Promoting Integrity in Global Water Governance

Encouragement, Challenges, Healing and Progress: The Baha’i Faith in Indigenous Communities

The Biology of Oneness: Achieving Health Equity Above the Skin and Below the Skin

Neurodiversity: A Key to Growth in the Faith

Reflections on Advancing Racial Justice Through Education

Understanding Interracial Unity in the American University

A Rich Tapestry

Glimpses into the Spirit of Gender Equality — Film Screening and Discussion

Paving the Path Toward Social Justice: Advancing the Discourse on Anti-racism in Medicine

We Are All One: The Role of Asians in Eradicating Anti-Blackness

Honouring the Children: Social Action for Truth, Reconciliation and Justice

Spirituality and society

Many sessions looked at the interaction of society with the spiritual nature of humanity:

“Biases get a bad name, but from a neuroscience perspective, all they are are mental shortcuts,” he said. Such shortcuts save time and energy in routine everyday life, not just in matters of survival and threat.

But trouble comes when the “lower brain,” seated in the amygdala, sees an “outsider” and reacts with hostility — and the “higher brain,” seated in the prefrontal cortex, isn’t applying “brakes” on that emotion, possibly due to stress. How, then, can people develop their higher brains to build resilience, creativity, empathy, and rewire their biases?

The Baha’i teachings prescribe some effective strategies for disrupting lower-brain impulses and increasing mindfulness, such as fasting, prayer and meditation, and putting oneself in the loving company of diverse people. “If you can welcome and embrace diversity, you can change your brain,” Radecki said, and genuine appreciation of a diverse world paves the way for building community.

The project has brought interested young people from across the continent together to study Baha’i guidance on the oneness of humanity and eradicating racism, then to team up and consultatively create recorded works and online programs — some of which have gained award nominations and other recognition.

As participants form networks in the conversation spaces that FRMWRK provides, Good said, they share their experiences in personal and community activities such as organizing devotional gatherings, teaching children’s classes, and helping with activities to benefit the hungry and homeless. “People get inspired by that, people ask how you did it, people start to do it in their own communities,” he said. Mentoring relationships are formed from there, in both artistic and human service activity.

Ritchie added that an important principle in the process of creation “is to let go of one’s ego … let go of some of the … ambitious tones and qualities and really embrace the idea of mutualism and collaboration.” (Click here for another glimpse of what FRMWRK does.)

Ideas, Religion and Social Change: The Baha’i International Community and the United Nations

Wings of Knowledge: Empowering Youth to Improve Their Rural Communities

Combating Corruption and Promoting Integrity in Global Water Governance

Knowledge Generation and Policy: Baha’i Perspectives and Emerging Knowledge Communities in China

A New Balance and New Direction: Reflecting on the U.S. Bahá’í Office of Public Affairs Advancing Together Symposium

Convergence: Cities, Spirituality and the Future of Civilization

‘Adasiyyah: A Study in Agriculture and Rural Development

Horizons and Mirages: What Lies in the Future of American Journalism?

Using Systems Science to Support a Learning Mode in Teams

Toward a New Research Program: An Interview with the Directors of the Center on Modernity in Transition

Fashion and Spirituality: An Examination of our Relationship to Clothing Beyond Consumption

Engaging Stakeholders in Research Endeavours: Process and Impact

Other topics

Several sessions dealt with the implications of Baha’i thought for specific fields of study, or the study of Baha’i writings themselves:

The beauty and multilayered symbolism of the original defies exact translation, she acknowledged — such as the depth of meaning even within the word ‘Ama, or “cloud,” in Islamic mysticism and prophetic imagery, as well as cultural and mystical references that would be familiar to 19th-century Persians with a religious education.

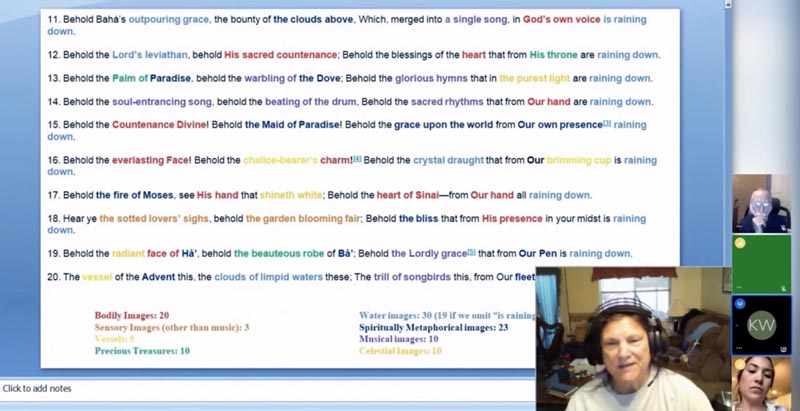

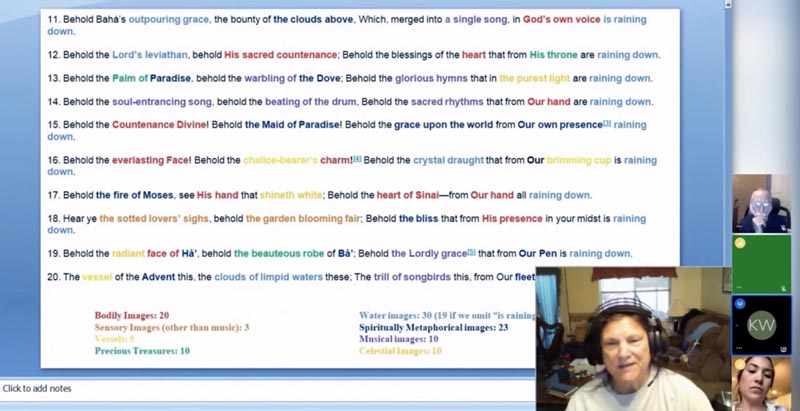

Her examination of each couplet of the English text touched on further symbols in Baha’u’llah’s announcement of the “raining down” of many blessings and wonders from God. It was followed by color-coded text showing the types of images used throughout the poem, including music, water, the human body, the senses, precious treasures, the heavens, and other symbols. The last few couplets, she noted, include strong exhortations “to whoever is reading the poem to … use all your senses to embrace what He is saying.”

Evolution, Design, and Faith

Science and Religion in Dynamic Interplay

Applications from Higher Education Research to Bahá’í Practice: Deepening, Action, and Reflection

Research Report: The Effects of Baha’i Prayers on the Moods of Undergraduate University Students

![]()

![]()

Whether you are exploring the Bahá'í Faith or looking to become an active member, there are various ways you can connect with our community.

Please ensure that all the Required Fields* are completed before submitting.