The pattern of community life has to be developed in places where receptivity wells up, those small centres of population where intense activity can be sustained. It is here, when carrying out the work of community building within such a narrow compass, that the interlocking dimensions of community life are most coherently expressed, here that the process of collective transformation is most keenly felt — here that, in time, the society-building power inherent in the Faith becomes most visible.

—Universal House of Justice, Dec. 29, 2015

The Collington Square neighborhood of Baltimore experienced growth in the pattern of community life on a particular block from 2010–2014. About a third of the street’s inhabitants have come to be involved in that pattern, and early social action initiatives have naturally emerged.

Since then, that activity has expanded into a two-square-mile area in the neighborhood. However, the focused experience on this single street offers a glimpse of what a united community can feel like in an urban setting as it advances spiritually and materially, through efforts to build a culture increasingly in harmony with Baha’i teachings.

The timeline that follows is adapted from a narrative written by a Baha’i who relocated to the neighborhood specifically to contribute to building of community.

2005–2009

Baltimore, population 600,000, is divided into numerous neighborhoods, some of which are sharply demarcated by race and economic status. From 2005 to 2009, local Baha’is learned from experience that a neighborhood in East Baltimore seemed to show receptivity to individual and collective spiritual and material development. This area has historically experienced disadvantages in housing, employment, and health relative to other parts of the city.

Initial receptivity to conversations was seen when a Baha’i began a neighborhood devotional gathering in 2005. Over a 14-year period, this gathering, hosted within a predominantly African-American community, brought together a diverse group. They prayed together, ate together, and talked about spirituality openly and deeply.

Learning: Devotionals can create a space for working toward the oneness of humanity and can develop an enthusiastic following. We learned how open our local friends and neighbors are to conversations about prayer and spirituality. When an activity takes place over many years, we saw that we develop together and our lives become intertwined.

Also in 2005, two youths volunteered to mentor children through an after-school program at an elementary school. Week after week, it became clearer to the mentors that neighborhood families accepted and embraced visitors who shared a genuine interest in their children.

Learning: We are all united in our desire to see our children grow and develop. As trust is earned over time, a vision of working together for our children can unite us.

Around 2008, Baha’is reached out in other Baltimore neighborhoods to invite residents to a devotional gathering. At times people answering their doors would ask, “Do you live here?” It became clear that trust was best built through living in the neighborhood, through truly being friends and neighbors.

2009–2014

In spring 2009, Baha’is of all ages carried out an outreach in an area near the home where the established devotional gathering was taking place. In the planning stage, the Baha’i community discussed frankly the reality that too many organizations enter a neighborhood and then leave. It was decided that participants in the outreach initiatives would need to commit to taking part in a long-term process, for years to come.

Learning: Children and junior youths can naturally be included in the outreach process and their participation helps all of us remember our focus on children. This is something we still do today.

In the next few weeks, the first group of friends played soccer in a park and held a children’s class with anyone who wanted to join. Holding the class outdoors on a blanket in the grass, for everyone to see and hear and join, made it easier to to create bonds of friendship. Some children would come and go, but a growing number joined in, whether brought by their guardians or on their own.

Learning: Being where people are, in open social centers, can help build friendship and trust more easily.

One neighbor accepted an invitation to join a study circle, with an eye toward being trained to teach a children’s class. Her husband joined her in the study, and before long she was helping organize and teach children’s classes.

As winter set in, a home a block away accepted to host the children’s classes and the two families in the home joined the training process. Invitations were also extended to neighbors near their house.

The following summer, a Baha’i and a friend made plans to move into the neighborhood. After much praying and searching, a home was found to rent on a corner one block away from the park. This home was at a spot with a lot of foot traffic.

Learning: When picking a location, visibility and access to people in the neighborhood may be features to consider.

Soon, the family that first hosted the children’s classes moved across the city. If the initial team hadn’t had a home, activities might have stopped at that point. As people moved in and out of the neighborhood, having a place became a safe way to ensure that activities continued, while more and more friends were invited to become part of the process of community development — and increasingly to take leading roles.

Learning: Where there is a high rate of mobility, the number of people invited into the process must be higher than the number moving from the neighborhood, or else activity will decline.

At that point, nine people were leading or helping with activities in the neighborhood. It sounds like enough resources to keep the process stable, but it took time to build ownership. And mobility is so high that seven of the nine ultimately moved out of the city. Activity became sustainable because the initial team worked to ensure it kept going until neighborhood residents had a chance to step into leadership roles.

Learning: Until friends in the neighborhood are teaching classes and tutoring study circles, more supporters might be needed if no one is full-time.

Rather than keeping the house locked at all times, as city-dwellers might expect, the team shared keys with all who were leading or participating in activities. This gave the house a community feel — that it was not a person’s but the whole community’s home. Friends described it as an oasis and enjoyed coming in to have coffee and read Baha’i books that were made available.

Learning: The Baha’is found it helpful to be completely open — indeed, radically open.

After a year, the children’s classes had grown. A youth came to the neighborhood as a full-time volunteer, and helped build many more friendships. Each day the youth and friends on the block got together to make breakfast, drink coffee, play chess and say prayers. This daily devotional led to a study circle.

Learning: Genuine friendship goes hand in hand with a shared vision of development.

Learning: The presence of a full-time volunteer can be of great assistance when other participants face time constraints. If a volunteer stays only for a year, it can be helpful that they focus on needs that others don’t have have time to fill.

Study-circle participants and other neighbors began a weekly devotional with dinner on Wednesdays. People from all backgrounds and life experiences were invited simply to “come over on Wednesday.” Dozens of people took part, and all were offered opportunities to join further in this new pattern of community life.

Learning: When devotionals are held weekly, invitations become easy and personal. Less frequent and it would have been more like inviting people to an event.

As the neighborhood developed, a new friend on the block brought children she looked after to the children’s classes. She progressed through training courses, became a children’s class teacher, and began hosting other activities and inviting neighbors to them. Within a month, she was hosting a Baha’i Feast in the neighborhood — a regular consultative, devotional and social gathering.

Learning: New friends can share this movement and process with many others. As more people are inspired, they share their experience and excitement. Eventually a chain reaction develops, fueled by friendship and prayer concentrated in a local area.

One day, members of a church across town came through the neighborhood and invited people to visit their services. A resident pointed to the Baha’is’ house and told the church members, “This is where we pray.” At that moment, it felt like the Baha’i household was really rooted in the neighborhood.

As more individuals taught children’s classes, hosted devotionals, and learned more about service inspired by the Baha’i teachings, their families joined them. Spouses and older children joined study circles. Children and grandchildren joined children’s classes and graduated into junior youth groups.

Learning: Families can have a significant impact on a community by serving through multiple generations. Mothers and grandmothers were in the front line, guiding this process forward.

After a year or two, three distinct groups in the neighborhood were sustaining a total of seven regular activities.

Over time, the initial group of Baha’is and friends celebrated birthdays and weddings and attended funerals together. They went to family cookouts and were introduced to each other’s extended families. After school, children came to the house to play, while friends and neighbors stopped by to say hello. Parents were comfortable knowing children were in a nurturing environment.

Through this process, the team gained experience with animating successive junior youth groups. Parents and children have embraced the junior youth program, which covers topics such as justice, the power of expression and developing spiritual insight. As a neighborhood we are still learning about raising and sustaining animators. But with a united team, challenges have been opportunities for learning and growth.

For example, after a father prevented his son from participating because of his religious affiliation, the ban had the effect of increasing curiosity among his son’s peers and attendance at junior youth groups increased to a point that couldn’t be sustained until more animators were recruited.

Learning: Even when opposition arises, it need not be feared.

Given how many insights and skills are nurtured throughout the courses of the junior youth program, how to advance through the course books has been a point of ongoing learning for us. However, we saw that once children who had been in weekly children’s classes, and thus were accustomed to memorizing quotes and praying collectively, reached junior youth age, these habits strengthened their engagement with the books.

Learning: A strong children’s class program can strengthen the junior youth program in a neighborhood.

During the youth volunteer’s period of service, his career development was not being ignored. While he was serving in the neighborhood, he spent a few hours a week gaining clinical experience at the nearby academic hospital. During that year, he applied to and was accepted by a medical school. Later, in medical school, the experiences from his period of service guided him to start a nonprofit organization with peers focused on community development and elevating the voices of members of a community in identifying their health needs.

Learning: Material and spiritual development of youth can both be considered in a period of service. If feasible, local support of youth volunteers can offer a customized plan that is flexible and builds capacity in various aspects of life.

After the service youth moved out, more people were invited to live in the homefront pioneer’s home and contribute to the community-building process, including adults and youths within the neighborhood. Over the past eight years, a total of eight youths and three adults have been invited to live in the house and engage in service. When friends came in with a vision of community building or a willingness to learn, they were able to engage effectively.

With five adjacent households praying together and helping weekly children’s classes, and about 16 people on one side of the block attending activities multiple times in this small space, love and unity were palpable. Importantly, a culture of service arose that spilled into other aspects of life.

Out of this process of the community coming together to reflect, consult and act, startup organizations or businesses naturally arose that began to address local needs. While some stopped, others have been sustained in various forms, offering lessons along the way. Broadly, these initiatives came to address issues of food, employment, health disparities, childcare, housing and land.

Learning: Social action is strengthened when based on a system of empowerment that strengthens spiritual qualities with service. Traditional methods of management and organization, if replicated without the application of spiritual principles, risk perpetuating factors that can contribute to injustice.

BMore Visible was one of those startups, founded by five neighbors to facilitate eye exams and glasses within a neighborhood where documented disparities exist. An “accelerator” program associated with a local business school asked one of the startup’s members to serve on its advisory board. It became an opportunity to contribute to the local discourse on how to approach neighborhood development and the value of human beings. Also, in conversations with friends, those serving in the neighborhood are able to contribute to how it is perceived and what development truly means.

2014–present

Five years ago, a series of events caused the future of activities in Collington Square to seem uncertain. Illnesses, accidents, death and structural damage to the rented home all raised questions of what might happen as the concentration of activity on the block began to be dispersed.

However, the bonds of friendship led the friends to continue moving forward and new doors opened. The head children’s class teacher from the neighborhood moved several blocks, to where many of the children lived. After the homefront pioneer looked for a permanent home to purchase in the neighborhood for activities, one became available on that same street.

It was a different kind of social center than before. Positioned at the entrance to a new school serving the neighborhood, it had access to dozens of families that walked their children to school each day.

From the early years the neighborhood held its own Feast, which was conducive to its development and identity. However, after years of holding Feast separately, the community decided to hold a single city Feast, now within this neighborhood.

To sustain the pattern of growth, efforts are being made in a larger area of the neighborhood to reach out and offer study circles. One of the original children’s class teachers now has a larger role in advising and encouraging the community in the process.

Two more people have moved into the neighborhood, within two blocks of each other, to serve as animator and study circle coordinator.

Learning: Over the years, the children’s class has been the engine of growth. It has helped people engage with the Word of God, built children’s memorization skills and helped parents connect as a community. With these activities sustained all these years, the neighborhood has seen children go through the educational sequence and grow up through the system.

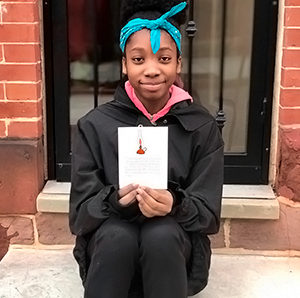

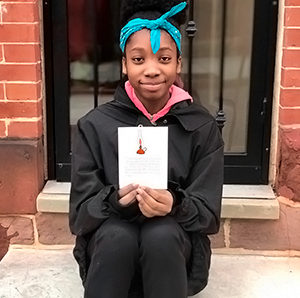

![]()

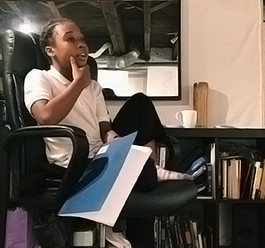

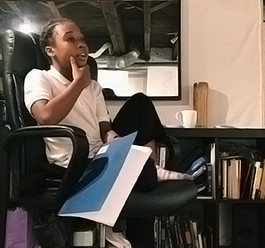

![]()

Whether you are exploring the Bahá'í Faith or looking to become an active member, there are various ways you can connect with our community.

Please ensure that all the Required Fields* are completed before submitting.