For all the progress that the civil rights reforms of the 1960s represented, they didn’t completely address the cracks in our country’s social structure, asserts author June Thomas. She says that Baha’is are now striving to find ways to do so.

“What was needed then, and now,” Thomas said, “are what Baha’u’llah’s Revelation brings and the true reforms that Shoghi Effendi wrote about” in the 1930s through 1950s.

Thomas spoke at the 2022 Association of Baha’i Studies conference on the topic “Racism and Racial Justice: Mid-century South Carolina,” sharing some of the research and discoveries that led to her new book, “Struggling to Learn: An Intimate History of School Desegregation in South Carolina.”

Her book, aimed toward a secular audience, is a historical description of a history of racial oppression and Black community response in South Carolina that, woven in at key points within the text, mentions Baha’i principles about race unity. Writing and researching this book demonstrated to her the flawed nature of civil rights reform of that era. In her talk, she cited relevant writings of Shoghi Effendi, the Guardian, leader of the Baha’i Faith from 1921-1957.

She also noted what the Universal House of Justice, the international governing council of the Faith, is saying now and how they both relate to the problems that existed at the time. Inherent within these writings was a clarion call for holistic social reform, covering much more than just voting rights or desegregated schools and opened public accommodations.

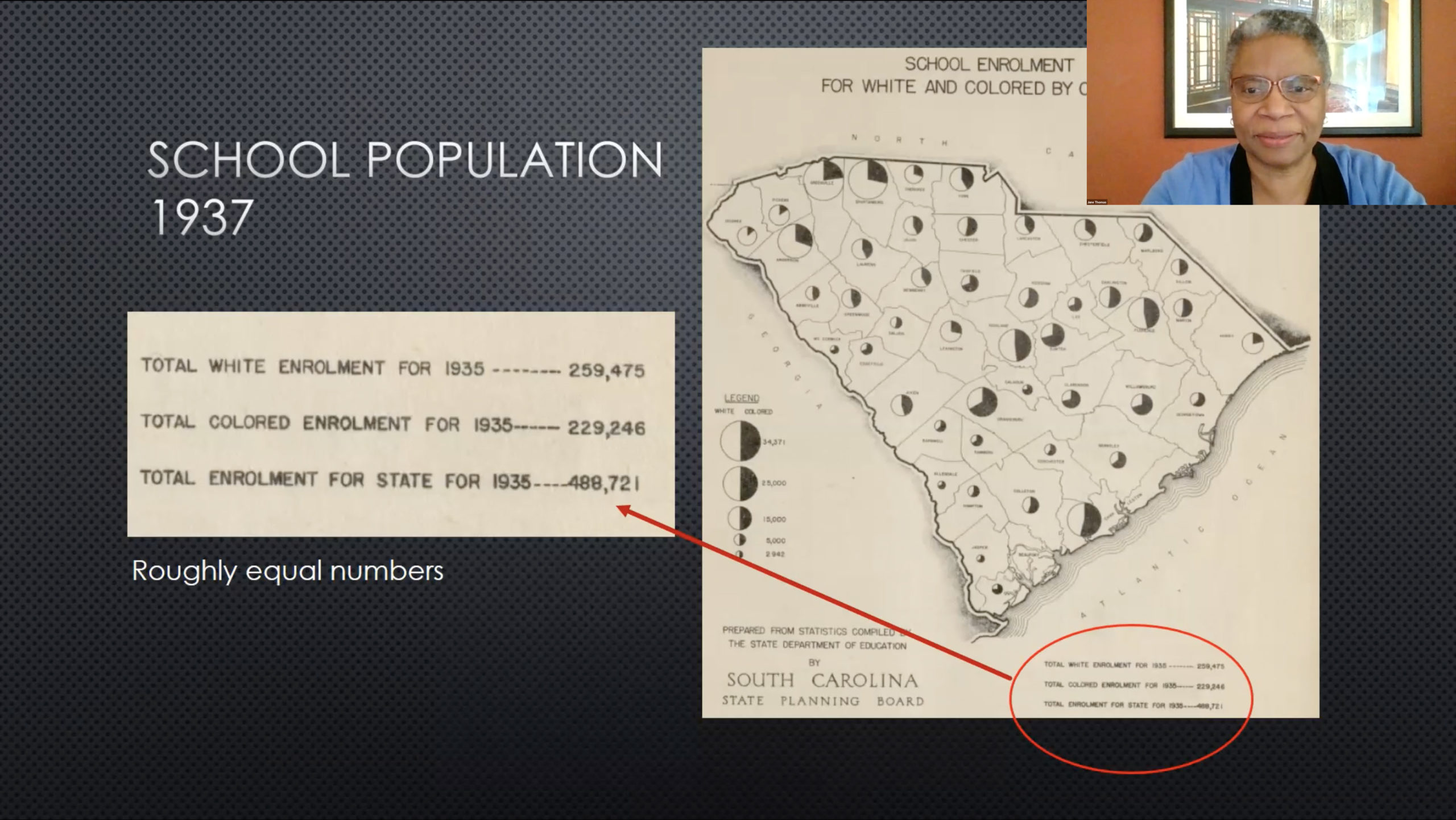

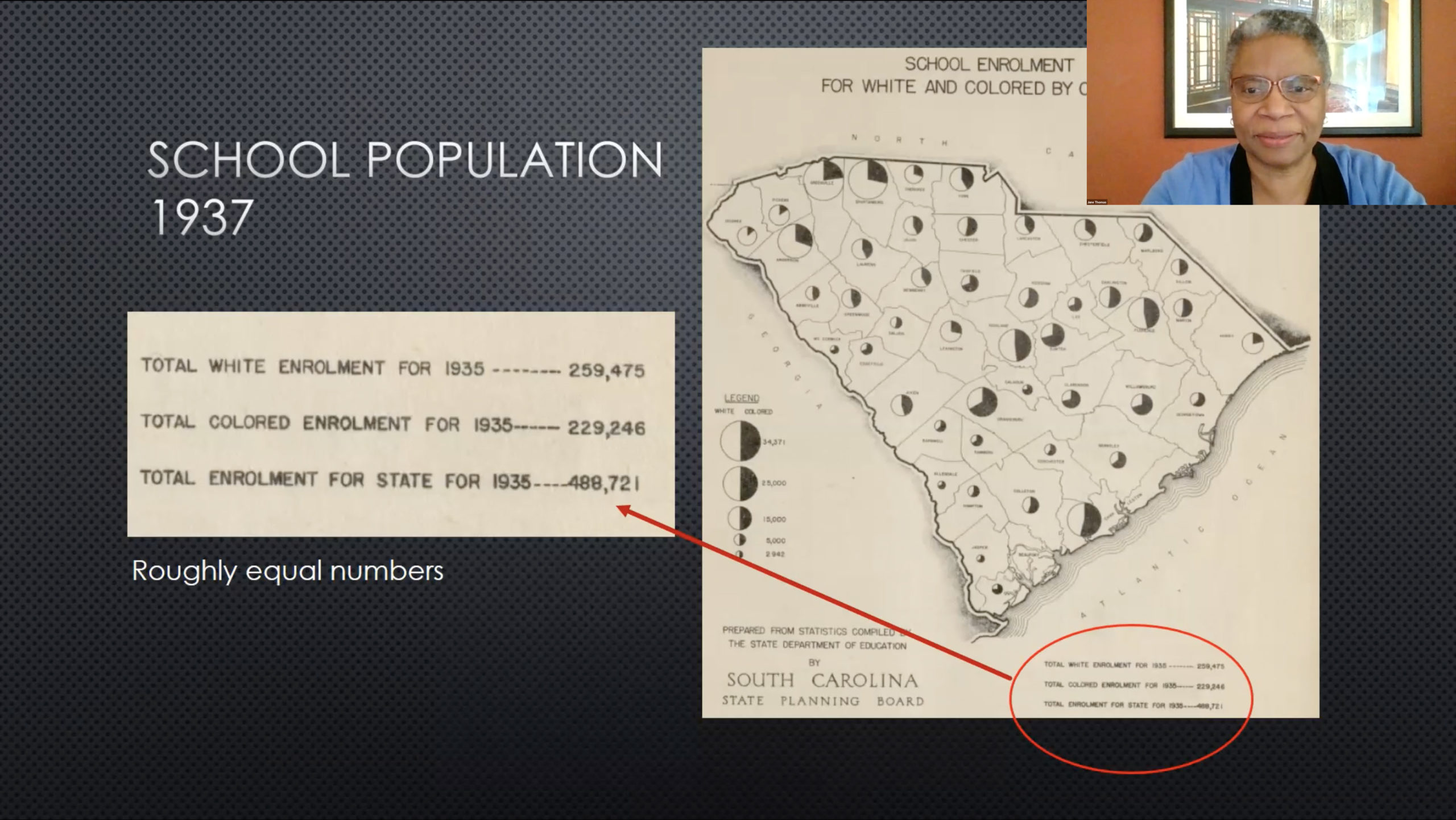

The doctrine of “separate but equal” regarding educational facilities was nullified by the Supreme Court in 1954. What followed, Thomas said, was a “genteel segregation,” with schools funded by an unequal taxation system. When challenged in courts, this new system was found to be unconstitutional, but no enforcement followed for many years.

At age 14 Thomas was one of 13 Black students selected to integrate Orangeburg High School in South Carolina. Orangeburg residents had previously carried out many boycotts and marches. These efforts attempted to address the racial divide in our country as a whole, and South Carolina in particular.

Thomas sees Baha’i children’s classes and the junior youth spiritual empowerment program as “alternative equitable education that supplements unequal education with equal spiritual education.” She also recognizes that the institute process — aimed at building capacity for service with the use of Ruhi Institute materials — gives educational tools to all people regardless of their formal education.

Asked how the institute process addresses the topic of race, Thomas said, “It allows us to have conversations about the oneness of humanity and how we are one people and see ourselves as spiritual beings who can love one another.”

Grounded in that principle and studying the Sacred Word together, “we begin to form the bonds of friendship and trust” and “can have honest conversations around race relations.”

Even when study materials don’t directly address race, “the friendships allow for things that are in people’s hearts. It works best if there are interracial study circles and children’s classes. Then the topic comes up!”

Integration alone, without a spiritual underpinning doesn’t solve the issue of creating racial unity. “It’s very easy to be separate and never live or work in a space with people of different races,” Thomas added. “It’s important to think about that and try to broaden our horizons and reach out to people from other backgrounds. Engagement in conversations and joint activities allows us to manifest love.”

![]()

![]()

Whether you are exploring the Bahá'í Faith or looking to become an active member, there are various ways you can connect with our community.

Please ensure that all the Required Fields* are completed before submitting.